Endeavour: A Space Trilogy

Three Movements for the NASA Expedition of Dr. Mae C. Jemison

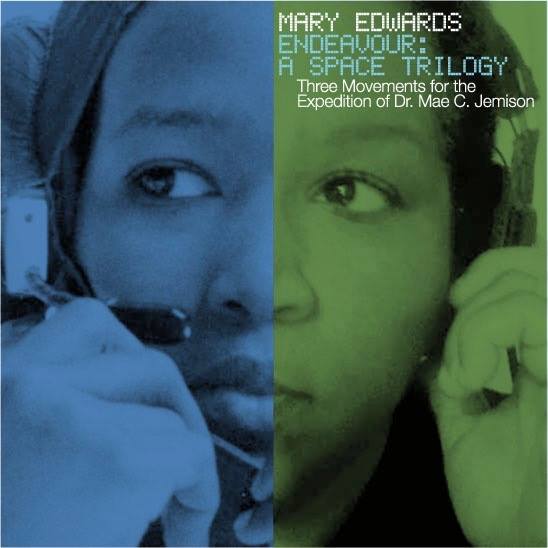

There is an iconic photograph of NASA Astronaut Dr. Mae C. Jemison, the first black woman to go into orbit on September 12, 1992 on the U.S. Space Shuttle Endeavour. The close-up of her expression reveals the determined and judicious aptitude one needs to demonstrate, with laser-focus and listening intent, to process the intricate instruction relayed to her from Ground Control. In my perspective, this image depicts a woman who, by taking the helm of her own cultural narrative, becomes the shuttle.

Relating experiences to being Black perpetuates “otherness”—there is a suggestion of singling out, or chance of alienation. When Jemison resigned from NASA in March 1993 to further research how social sciences interact with technologies, NASA training manager and author Homer Hickam later expressed some regret that she had departed, saying, "NASA had spent a lot of money training her; she also filled a niche, obviously, being a woman of color." In a later interview, Jemison’s response was that she was not driven to be the "first black woman to go into space….I wouldn't have cared less if 2,000 people had gone up before me... I would still have had my hand up, 'I want to do this.’”

There is a correlation among Jemison, her inspiration for joining NASA, actress Nichelle Nichols, who portrayed Lieutenant Uhura on Star Trek, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that exemplifies this interchange between epoch-making responsibility and the construct of societally imposed differentness.

As a child of the ’60s whose love for, and exploration of space, science and nature was evident, Jemison, inspired by both the Apollo flights and Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches, felt King’s dream was not an elusive fantasy but a call to action, of, as she once stated, “attitude, audacity, and bravery. The best way to make dreams come true is to wake up.” The civil rights movement was all about breaking down the barriers to human potential. On Star Trek, Nichols gained popular recognition by being one of the first black women featured in a major television series to have a technical role. In a conversation with Dr. King (a big fan of Star Trek), a reluctant Nichols was personally encouraged to stay on the show, and not give up playing a vital role model for black children and young women across the country, as well as for other children who would see blacks appearing as equals. 'You can’t [leave],” urged Dr. King. “You're part of history.”

From the mid-20th Century, women of color have been responsible for mathematical calculations and scientific formulas that facilitated the NASA astronauts’ successful space launches and landings. But as both the book and film title, HIDDEN FIGURES (2017) implies, these important women were long obscured from the greater historic and cultural context. Perhaps, if we were made privy, through our formal education—in real time—to these brilliant contributors to the advancement of aeronautics and aerospace travel (as with other fields), Dr. Jemison’s achievement might be viewed through an egalitarian lens, as the vehicle that symbolically shuttles her between the two worlds, becomes obsolete, and that the conveyance of her greatness is a well-maintained and choreographed poetic justice.

My portrayal of Dr. Jemison’s mission is a composite recount, created in an orchestral, cinematic arc in which it poeticizes rather than politicizes an historic event, where, as Dr. Jemeson emphasizes in her own practice, the arts and the sciences are not two separate entities, but rather converge to inform and convey to you, the listener, an awareness of temporality, impermanence and passage.

This work, in its entirety, is comprised of three parts: The first and third movements (The Ascent and The Descent) subtly reference Afrofuturistic reclamation through interspersed rhythms and melody (and Dr. Jemison’s early aspirations toward ballet), with a chorus of sirens incanting a version Dr. Jemson’s sentiment upon arriving into the stratosphere (“The first thing I saw from space was Chicago, my hometown”), bringing her personal mission full-circle to her childhood expectation that she would someday embark on an intergalactic mission. This homage is reflected in an opening and closing theme reminiscent of a Mid-Century Library Music score, while the second movement (The Suspension) is, in essence, the satellite, breaking away from the whole to become a meditation, an organic devotional, and a prologue to the environment-as-orchestra: The melding of subtle bodily sounds, disembodied voices, humming, intonations, and vocables, which upon closer listening, reveals an infinitesimal harmonic universe.