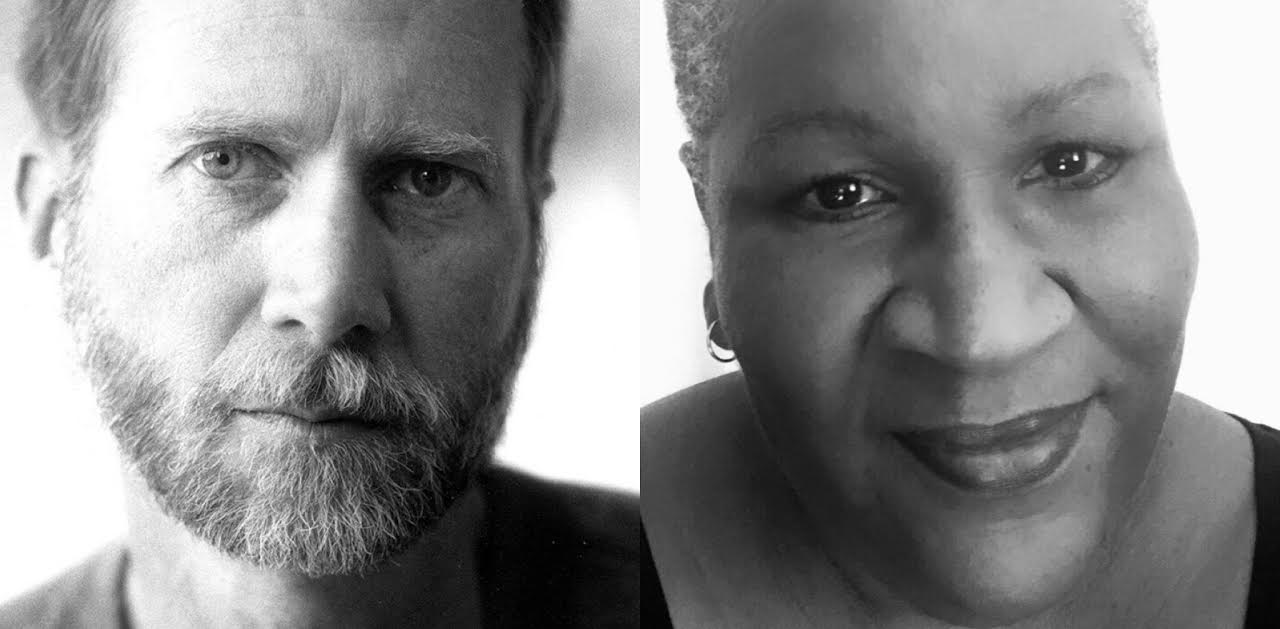

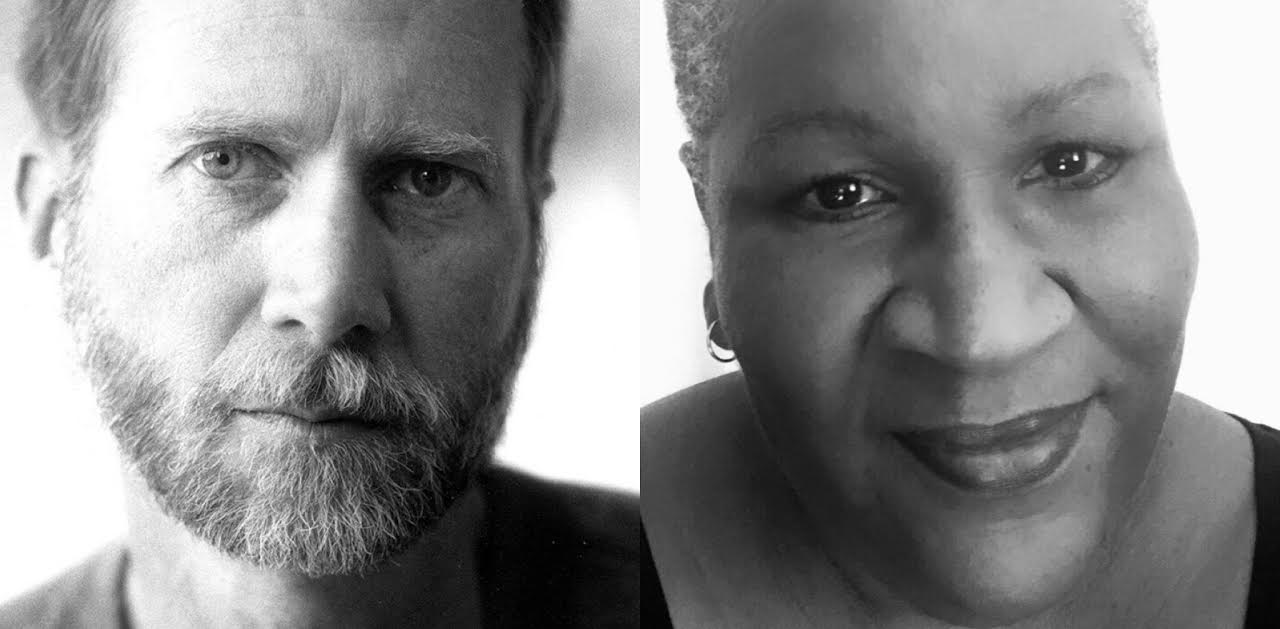

Mary Edwards on

John Luther Adams

I have been fortunate enough to have a variety of mentors, teachers, collaborators, and what might be called cultural godmothers and godfathers, all of whom have informed and inspired my work in music over the years. Paradoxically, a few of the most influential mentors I have had are the ones that I haven't known well, if at all. But the sense of direction, permission or possibility these “distant mentors” offer can be profound. My connection to the person I chose to write about here, the contemporary American composer John Luther Adams, exemplifies the way even someone who we don’t know or interact with personally can still transform not just the actual work we produce but the way we think about that work, our process and our world.

A theme that has run through my music from the beginning, becoming more central over the years, is the idea of immersive sound experiences: sound as an enveloping temporal, spatial, even architectural form. Some 12 or 15 years ago I was working with academic mentors who encouraged me to think outside the box in terms of genre and what I wanted to do with my music. I remember one of those mentors, the composer Laura Koplewitz, saying something like, "Okay. You’re writing these pieces about airports. You're writing these pieces about the woodland experiences. Have you considered sound installation?"

In response, I began to investigate artists working with sound installation and other intermedia forms, John Luther Adams among them. I learned about Adams before he won Pulitzer and Grammy awards and also before it was possible to find and hear most pieces of music with a digital click. He had a respected name among contemporary composers but his work was something you had to seek. I sought out and listened to his music and gradually learned more about him and his career. His story, sensibility, and music resonated deeply with me.

Like me, Adams is originally from the New York area and has what in some senses is a typical musical background: he wrote music, he performed, he taught music. But his career has also been transformatively shaped by his passion for environmental causes, particularly after he moved to Alaska, where he lived for decades until a few years ago. Interviews discuss the moment in his life when he felt that he had to choose between focusing on environmental change and focusing on music, both of which are consuming careers. He felt that he could best serve through his music—an intuition that has certainly proved true. His music is profoundly influenced by the natural world, the threats to the planet, and what he’s called “that region between place and culture…between environment and imagination.”

Among other things, my exploration of his work affirmed the possibilities inherent in my own fascination with place and my interest in forms such as what’s called aleatoric music. In the Western canon, we expect to hear a piece of music that has a beginning, middle and end and that is performed in largely the same way each time. Aleatoric music works differently—Werner Meyer-Eppler, who coined the term, said that it involves a course of sound events that is “determined in general but depends on chance in detail.” “Noises” considered distractions in the performance of a piece of traditional music become part of the experience in work that’s not meant to be performed in a concert hall. The assumptions about how we should hear things and what we think we know are challenged, and our inextricable and often complex connection to a particular place is affirmed. We are not so much listening to a pre-existing work but going on a journey to new and deeper levels of ourselves. All of this and more moved and inspired me as I explored Adams’ work. Many of these thoughts and threads came together when Kathleen Hancock, director of the Grimshaw-Guidewicz Art Gallery in Massachusetts, comissioned me to to create a composition and sound installation a few years ago. I have always been interested in geography and bodies of water and I knew that I wanted to do something specific to this particular place. The piece I created took as its starting point the Quequechan River, one of the network of waterways of the Fall River area, where the gallery is located. At one time crucial drivers of the region’s industry and commerce, rivers like the Quequechan were later depleted, polluted, and made invisible in many senses of the word. Now people are interested in bringing back the Quequechan and other rivers like it.

For my piece, I researched the history of both the area and the river. In addition, for almost six months I visited the river one weekend a month and recorded different points in its course. Not all of the Quequechan is accessible—a significant stretch of it has been covered up by I-95. But enough of it could be experienced for my purposes. In one early visit in January 2013, I recorded the ice breaking up and melting, the sluggish movement of the water. I recorded the more rapid, flowing motion of the water as the seasons changed and also recorded at the Fall River cascades, around which some of the old industrial mills and warehouses still stand.

In my studio, I used an audio program to weave the recordings together into a 14-minute piece. Orchestrated with a series of musical motifs, it creates the sound illusion of traveling the length of the river, going through its different parts and its different points. I juxtaposed vocal sounds with and into that, haunting voices that suggested those (both old and young) who worked at the area's mills in their heyday. I wasn’t interested in being literal or in making an explicit political statement of any kind. I wanted to capture the sense of the memories the water still carries, its characteristic “speech,” and its complex environmental relationship with the human communities through which it runs.

My piece, which I entitled per/severance, was installed in the gallery in tandem with a work called This Bright Morning by the visual artist Charlotte Hamlin. You could stand under the mysterious, evocative root shapes she suspended from the ceiling and hear, in my piece, the sounds of the river. During the opening at which per/severance premiered, a woman whose family had lived in the area for many generations, and who had found out that I was the composer and sound artist, came up to me. She threw her arms around me, crying. She said, "Thank you for giving the river a voice.” It was such a lovely moment, and one that reinforced my sense of creative direction. Built around three very different settings, my most recent work, The Space Between: A Sound Trilogy, uses sound to investigate the tensions between essence and impermanence, desire and uncertainty, nature and architecture, and absence and presence. The sense of possibility that listening to John Luther Adams has given me, and the example of the way he builds on elements of chance and place, are very much part of what inspires and underlays this trilogy as well as the other pieces emerging for me now.

I was fortunate enough to attend the New York City premiere of Adams’ work Become Ocean, which went on to win the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music, and to meet him briefly at that time. About a month later, I attended a music conference in North Carolina. There I was invited to participate in a 40-person percussion outfit performing one of John Luther Adams' pieces, Inuksuit, outdoors on the campus of the University of North Carolina in Ashville. Adams the person was not present, but Adams the thinker, composer and environmentalist was very much in felt and appreciated. For me, the chance to help perform a composition by this mentor who has been so important to me– to inhabit, as it were, from the inside–was a moving and unforgettable experience.